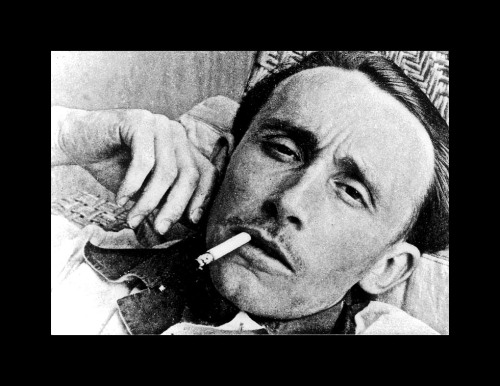

FILM CRITIC THEORIST André Bazin

Introduction to André Bazin, Part 1: Film Style Theory in its Historical Context

Introduction to André Bazin, Part 2: Style as a Philosophical Idea

By Donato Totaro, Offscreen, Vol 7, Issue 7/July 2003

I can see in a previous post a link to part 1. Since these two popped up recently, thought is good idea to have the links in one place.

Also:

Back to Bazin Part 1: The Ontology of the Photographic Image

2008 post in Spectacular Attractions.

If you fall into the who the hell is Bazin category, or I’ve heard the name am a bit vague on his ideas, it might well be worth a quick zip through Dan North’s first para before tackling the Totaros. Or even sticking to it all the way through. He has included useful links including the Totaro. It all goes round and round.

Cruelty and Love in Los Olvidados

by André Bazin

In: The Cinema Of Cruelty, Arcade Publishing, New York, 2013.

Posted by Eduardo Carli de Moraes in his blog, Awestruck Wanderer. His latest post highlights Jo Sacco’s graphic novel, Palestine. Lots of interesting posts and check the side panel.

FILM GODARD A Man, A Woman and a Dog

![FILM GODARD Au Adieu au Langage [iPhone]](https://adferoafferro.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/film-godard-au-adieu-au-langage-iphone.jpg?w=540&h=375)

{1}

Godard has a new film out. And he’s keen/anxious to talk about it, film ‘n stuff.

A few people have seen it, writing and talking about it at great length so spoiling it for everyone else who might have wanted to see it without the comments and interpretations of the expertigensia ringing in their ears, at what you now know are salient or significant points in the film [or the homage points, say, to his own films or film in general] which you’d hope to enjoy, be puzzled or exasperated by at your own pace.

Thank God (the one without the full stop or as the French call it, point, a word J-LG could have a field day with…). I made sure I did not read a lot before watching The Great Beauty. And then when I had seen it, I desisted from even translating the title into Italian or even mentioning that the phrase had been used by a character in the film in a certain way. See, there I’ve done it now. Now you will be on the look out for it, even though there has been no indication why this might have some significance.

One reads the contents of one’s mind before seeing a film, in anticipation of it, which in itself may spoil a film. Book, art, play, film. A filmic or booky equivalent, shall we say analogy, to phenomenological bracketing or epoché is impossible. I’ve already remarked in a recent post that as soon as I saw the poster for The Great Beauty, I knew [as would literally millions of others..] where we were coming from, though not necessarily where we were going to. Eric Morecambe’s famous riposte [applicable to almost anything, like the Actress & the Bishop jokes] to Andre Preview on his, Eric’s, terrible rendition of – was it Grieg’s piano concerto? – “I’m playing the RIGHT notes, but not necessarily in the RIGHT order!” always flings itself up from the recesses of my mind like the lyrics to an incomprehensible ’60s songs like the one by Noel Thingy called The Windmills of My Mind.

Why it is that I think of J-L Godard as the archetype (or prototype) of the incredibly difficult (but obviously highly intelligent) au contrarian conversationalist in any setting – uncle [ton ton] J-J at a family wedding or diner party, seated next to you in aircraft, etc. – who somehow manages to create the immediate suspicion he may well be mad, or temporally cured and released from some sort of mental institution (the old jackets…), yet, underneath the frightening persona, has something interesting to say which holds you there despite your inclination to run.

Really mad people we seem to have an instinct for as we have so much experience of them in everyday life. Like films we have seen too much about before watching them, Jean-Luc Godard comes with such a pedigree, a provenance, we are comfortable in the paradoxical nature of many of his pronouncements. Expect them even. Be lost without them, possibly. We know he, like a lunatic, assumes you know he is God [when it comes to film]. If you do, as he knows he is and you do, then all is simple.

The reviews on Adieu au Langage were not out when I was passed by Glen W. Norton, via a Godard forum, the link to the Canon video interview avec Godard with English subtitles

(…a classic God[.] subtitles joke in there not created by God[.] himself. Qua? Comment? These are accurate subtitles while his are notably unreliable.)

The areas I forced myself to listen to, while going Ni Ni Na Na with hands over my ears [mostly], were the technical ones. And this is reflected in graphics included in the post. Let’s try to grasp (as it is obviously important) why he at one and the same time decries technological advances and at the same time adopts them with alacrity. Except that is, in the case of editing (See relevant tab on the canon interview page) where he it is explained there – something know amongst God[.] watchers – he uses magnetic video tape to edit with, thus getting his technical collaborators who have filmed digitally to make video tapes for him to edit. The amusing thing is he’s renowned as an expert in editing with tape to an extent that makes many scratch their heads at his ingenuity.

I use this digital-magnetic example as a route into the mind of Jean-Luc Godard, in a sense prior to any messages he may be sending to his avid (an even not so enthusiastic) followers about life in general and of course the art of cinema, and Art.

While he argues here about his latest film that 3D is a FWOT

(Along the lines of, “It is useless! We see no more with it than before..” All true of course.)

he still uses it (At least twice so far..). And presumably this is a way of saying something. Well of course it is. And here is where we get to the crusty old uncle who frightens the sh** out of you, who blows cigar smoke into your face, and yet who let’s drop those few words which catch your interest. Words you know are true like you know a word of art by a master is true without being quite sure how to explain it.

With Godard it is for me when he talks of art. If you knew nothing about Godard the film genius and heard him talking of art in relation to all sorts of things, you will be gaining an experience of the mind of a man who has thought very deeply about his art and craft, film. Filmmakers who talk photography are in the same area. Even the knowledge that a film-maker was formerly a photographer says a lot.

The one who now always comes to my mind, when film and photography are mentioned in the same sentence, or should we even say thought in the same thought, is Nuri Bilge Ceylan. And if I may take a God[.]-like excursion down an dark alley which neither you the reader nor I may quite know is a dead-end or not – as this post is as ex-tempore as you are likely to get in postdom – Ceylan, has used severally the trope of bloke-wandering-around-ancient-site-with-camera-ignoring-and-annoying-girlfriend trope.

With Godard we have to understand that every film is the same film because he is trying to get over the same God[no .]-like message about how he as God [with or without .] can use film to get over his agendas [or not]. And so could everyone else to humanity’s general betterment, if they only had the brains and foresight to see. He like many good or even great film directors [even nerdy-looking baseball cap wearing ones..] is steeped in film from the year dot. And he evokes the complete history of film almost in every quakey sentence he utters. It’s always, “What is film?”. And of course, “What can it do and not do?” He seems to be saying all the time, “Film can’t do/isn’t doing so many things that people dreamed it might do.” And that’s because they don’t understand it well enough to see its talents.

Godard’s “cinema is dead” or “It is now!” [UK football ref there you no UK people..], or “Well, I thought it was then but it really is now” can confuse people. But it’s simple. He believed like Eisenstein that film was purely for political ends. The montage was the method. The Way, The Truth and The Light.

And so fast forward to a film like Adieu au Langage [3D]. Just like me with my immediate and deep apprehension of the depth of Italian cinema through a balding man sitting on a classy bench with shades that look suspiciously like the Ray-bans Marcello Mastroianni wore in 8 1/2, we should get the fact that every time Godard speaks on film (and life) he is thinking of how film failed. He may talk enthusiastically and yet mockingly or ironically about advanced technology, but you know he is still trying to get there, by any means at his disposal.

And all the time, he is still using the same film-text-film-text-text-film-film he developed from his earliest films. At one point in my Godard journey, I felt sure he was saying film could not replace writing and so his films had to constantly show this to be true. For the audience this can be both irksome and difficult. A major facet of this is his voice and text overs are in French. Unless French is your first language or a good second, his efforts to overlap three things at once are pretty much wasted on you, as an immediate effect.

If this all seems a bit too arcane and you have not got to Histoire[s] du Cinema (and perhaps never will) try reading Celine Scamma’s schema for Histoire[s] – a blog search in COTA will get you there.

And finally, as The Two Ronnie would say, there is that thing about Godard and his unreliable subtitling. Apogee: Film Socialism. I have no idea whether this is true or not, but I sense he is saying that you can’t translate poetry into another language without destroying or partially destroying its original meaning. Which is true. Godel, Escher Bach, for some ideas and background. And he quotes poetry a lot in his films. As well as showing and talking about art.

And so for film. The very act of trying to make a film helps to remove your original intention (He seems to be saying..amongst many other things). If you just use film. So he, wanting to be sure of getting over whatever message he intends, falls back on words in films as text and commentary (plus the obligatory art),which in itself is an essay on the limits of film. Or the dialectic between The Word and The Film. (Being some kind of Marxist, he would want to show that dialectic is real moving things forward).

And so (and here back to latest interviews) he feels he can’t say directly (and never could or would) simply, in words, what he wants to say about film. This is both because it dishonours film (and maybe dispels some of its magic and mystic) and because he doesn’t want to make the whole thing seem simpler than it is. Instead he picks up on small points (in the Canon interview he starts with SMS, the modern, the dubious) from which to expand (why not start anywhere?) outwards and back inwards at the same time, to the core of what he sees film is and can do. And of course what life (using an iPhone) is and can mean (film your day he suggests..). That goes without saying. Though, like God[.], I’ve said it to make sure you don’t miss it.

Other

With Canon interview spoiler…

1/. Godard comes in many shapes and sizes

– He briefly reprised his views on aspect ration with Gallic hand gestures demonstrating the cutting off of the upper part of a shot, etc.

2/. Something I feel strongly: what a film is about or meant to be about can be taken separately from how it was made. Or not. They can complement each other. Or not. My natural inclination is to run these in parallel. Weaving in and out. Often when the going gets tough on the film itself as a story with a narrative imperative (or not), resorting, or even retreating (out of the sun into the shade..), to the How Did They Do That? seems the most sensible place to go. Even if in the end that strip of bright sunlight between the shady tree and the house has to be crossed.

Godard is often talked about in terms of his oeuvre when a new one pops up (as one does of directors in general). We get the jump cut standing for À Bout de Souffle, or Fritz Lang standing for Le Mépris (who starred in it but to whom Godard was also paying obeisance to as a director. (Wiki:Contempt (film) is an Idiot’s Guide to the latter with some of the associated Langifications – A browser search on Fritz on that wiki page will do the trick).

FILM COURSE BFI PASOLINI The remains of the study day

Image from Brian Matthews’*Movie Ramble

Pasolini Study Day at the BFI.

The talks and discussions have been made available as free pdfs at iTunes, where the course is described as

Stimulating and engaging programme of talks, discussions and screenings (hosted in collaboration with the University of Sussex’s Centre for Visual Fields and School of English) exploring the work and thought of Pasolini, one of the greatest filmmakers of his generation and a fiercely original – and controversial – public figure. A prestigious line-up of speakers includes Adam Chodzko, Rosalind Galt, Robert Gordon, Matilde Nardelli, Geoffrey Nowell-Smith, Tony Rayns, John David Rhodes, Filippo Trentin and his favourite actor: Ninetto Davoli.

Singled this out from Catherine’s Film Studies for Free

She’s provides a mountain of a film resource, but I find a lot of the academic stuff largely incomprehensible and distracting from film itself. Love film? Watch films.

* Brian has done some posts on Pasoli’s he’s watched

FILM ESSAY NICO BAUMBACH – All that Heaven allows: what is, or was, cinephilia

All that Heaven allows: what is, or was, cinephilia [part 1]

All that Heaven allows: what is, or was, cinephilia [part 2]

Film comment, Film Society Lincoln Center, 12 February 2012

At time of this post two further parts were promised

Part 1 quotable quote:

Bordwell’s argument is framed as an attempt by an academic to reach out to film critics not simply to heal a rift but to mutually enrich both practices. Yet more interesting, and problematic, he outlines what writing about film can successfully accomplish and what it cannot. He implies that the opposition between academics and critics obscures a more fundamental opposition between two different ideas of what the primary object of writing on cinema should be — its relation to culture and society or to the more localized specifiable effects that films produce. He believes that by ignoring the latter in favor of the former, film criticism and theory have lost sight of their object.

Part 1 mentions Laura Mulvey’s 1975 essay, Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema

There is a digital cross-through in this version, so I’ve included a couple of other sources: LM 2 and a facsimile of the original article/paper: LM3 (which in a footnote says it’s a reworked version of a paper given in the French Department of University of Winsconsin, Madison, in the Spring of 1973

Baumbach quotes Mulvey:

“It is said that analyzing pleasure, or beauty, destroys it. That is the intention of this article.”

which he then goes on to explain, including:

..her statement came from a conviction that theory about cinema mattered not just in relation to gaining specialized knowledge about a particular popular art form, but to how we live and experience the world.

FILM E-BOOK How to Read a Film by James Monaco [in chapter sections]

How to Read a Film

By James Monaco (First published 1977)

Chapter 1. Film as Art

Chapter 2. Technology: Imagine and Sound

Chapter 3. The Language of Films: Signs and Syntax

Chapter 4. The Shape of Film History

Chapter 5. Film Theory: Form and Function

Chapter 6. Media: In the Middle of Things

Chapter 7. Multimedia: The Digital Revolution

FILM ANALOG / DIGITAL # 1 – Godard

Oui or Non? (22 December 2010) in blog Godard Montage starts with a screen grab of Godard, with its subtitle in English, Can the new little digital camera save the cinema?

It’s only a short post:

Godard is correct I think not to respond to this question. There is a pause, a moment of silence, and then a cut. The question, in an important sense, is not for him to answer (and it’s a nice touch that the lighting of this shot doesn’t allow us to search for an answer in his facial expressions). This is a question for the next generation of filmmakers and artists. Oui ou non? They must decide – or, by not deciding, fail.

Although the post doesn’t say it, the still comes from Godard’s 2004 film Notre Musique.

There’s a YouTube of the scene without subtitles:

Jim’s Reviews at Jim’s Film Website does a full post on Notre Music:

A student now asks Godard, “Can the new little digital cameras save the cinema?”

One Plus One

Eric Hynes on Jean-Luc Godard’s In Praise of Love

No date on this post.

“Film Socialisme” was shot in digital:

CANNES REVIEW | Oh God(ard): Is “Film Socialisme” the Scandale du Festival?

by Eric Kohn (May 23, 2010)

In Cinemascope:

Spotlight : Film Socialsme (Jean-Luc Godard Switzlerland/France)

Andres Picard

Film Socialism: The Gold Standard

by

Richard Brody, New Yorker, 1 June 2011

FILM Deleuzian Film Analysis: The Skin of the Film

Deleuzian Film Analysis: The Skin of the Film

Donato Totaro, 30 June 2002

FILM GODARD Le Mépris: Analysis of mise-en-scène

Le Mépris: Analysis of mise-en-scène

By

Roberto Donati

in

FILM THEORY BAZIN ~ Monsieur Hulot and Time

by

Andre Bazin

translated from the French by Bert Cardullo. ? {1} or {2} {3 – books by}

FILM ESSAY – The Eye, the Brain, the Screen: What neuroscience Can teach Film Theory

Paul Elliot, “The Eye, the Brain, the Screen:What Neuroscience Can teach Film Theory”

Excursions, Vol 1, Issue 1 (June 2010), 1-16

FILM LINKS Slow Cinema and the Long Take

To add to my collection of posts on the long take, one from Either/Or/Bored, titled, Slow Cinema and The Long Take.

Nagging feeling it is already mentioned in a previous post. What the heck.

Links in there to: Top 15 Amazing Long Takes (and onwards to other film lists), Pasolini’s essay, Observations on the long take, which Janice Lee has on her page here. Jancis wrote, Damnation (2013), an ekphrasis and then some – with very good introductory and post-script essays by others – inspired by the films of Bela Tarr and the novels of Hungarian novelist László Krasznahorkai, who Tarr worked with on adaptations of his books including Satantango and Damnation. Lee includes impressive frame by frame after the event sketches at the back. For anyone who has frame grabbed a bit to get to grips with a film, the effort was admirable, spoilt only by the sketches being a bit too sketchy to work from, apart from each having an exact timing. So if you’re into Tarr you can watch the movies and look for the time yourself from hers to see what each was referring to..

Must already be linked to somewhere else in COTA. Who cares, a blog is a searchable database.

Mark le Fanu’s, Metaphysics of the “long take”: some post-Bazanian reflections, and to a film mag 16:9 essay by Mathew Flanagan, Towards an Aesthetic of Slow in Contemporary Cinema. Also, the first pic I have seen of Bazin. Didn’t imagine him like that at all.

FILM THEORY Michael Haneke’s cinema: the ethic of the image by Catherine Wheatley

Michael Haneke’s cinema: the ethic of the image

By Catherine Wheatley

This GoogleBook has available almost the whole of the chapter on Caché (Chapter 5: Shame and Guilt – Caché, and the whole of the 12 page introduction.

Michael Haneke’s Cinema: The Ethic of the Image by Catherine Wheatley

by Yun-hua Chen

explains what the book is about:

* It proposes an ethical theory of spectatorship

* Wheatley, in her examination of Haneke’s authorial persona, poses the rarely reflected-upon question of the origin, function and particularity of unpleasure in Haneke’s films.

An unpleasure profound enough, perhaps, to make one decide not to watch certain of his films. I’ve seen Caché, Code Unknown and The Piano Teacher, in that order, and don’t think I’m going to watch Funny Games or Benny’s Video. My final Hanke might be The White Ribbon.

The book cover :

Existing critical traditions fail to fully account for the impact of Austrian director Michael Hanke’s films, situated as they are between intellectual projects and popular entertainments. In this first English-language introduction to, and critical analysis of his work, each of Haneke’s eight feature films are considered in detail. Particular attention is given to what the author terms Michael Haneke’s ‘ethical cinema’ and the unique impact opf these films upon their audiences.

Drawing on the moral philosophy of Immanuel Kant and Stanley Cavell, Catherine Wheatley introduces a new way of marrying film and moral philosophy, which explicity examines the ethics of the film viewing experience. Haneke’s films offer the viewer great freedom whilst simultaneously imposing a considerable burden of responsibility. How Haneke achieves this break with more conventional spectatorship models, and what its far-reaching implications are for film theory in general, constitute the priciple subject of this book.

FILM TECHNIQUE parametric narrative

by Colin Burnett [Senses of Cinema]

David Borwell’s Narration in Fiction Film {GoogleBook}:

Chapter 12 . Parametric Narration

Most of chapter

Chapter 13. Godard and Narration

Just the first page and a bit, but worth having.

Narrative in Fiction and Film by Jocob Lothe {GoogleBook}

Most of the first 36 pages of the introduction.

From FilmReference.com

FILM THEORY Auteurism

This post will be for a range of links to this subject. Starting with Girlish’s On Auteurism post [30 Marc h2008] , which has an enormous comments stream.

FILM FRENCH BRESSON The Devil, Probably {Le Diable Probablément} (1977)

“The movements of the soul were born with same progression as those of the body.”

Montaigne*

The region 2 Artificial Eye DVD has a filmography but no extras.

This is my second Bresson. Though I’ve watched The Pickpocket on YouTube. I’ll probably get the lot for my collection, but Bresson’s use of amateur actors is still unsettling. Who hasn’t watched a Bresson imagining the parts done by professionals and been distracted from the film in the process? Having commented on his style after watching Au Hazard Balthazar, I feel a strong urge to do so for this film, in other words. And to make some progress in understanding Bresson’s purpose and meaning.

This time the word tableau(x) came to mind (if that is the right word…). Yes: tableaux vivant, which is sufficient to suggest where Bresson is coming from. He was a painter before becoming a photographer before becoming a film-maker. It is also interesting to learn how many other film-makers use/d tableaux vivant.

Maybe Bresson thought he could somehow ‘translate’ still tableaux into a moving ones. If so, I don’t think it always works because – as if a sort of phenomenological epoché** was required – the viewer is being asked to put away much of what exists in the real world. People cough, splutter, grimace, scratch, gulp, check on what others are looking at and saying, relive recent events by relating them to others.

Bresson’s characters are made to look into the middle distance even when talking to someone quite close-up.

The hardest thing to take in a Bresson film as a viewing experience is the artifice in the acting. But then again plays are often highly stylised and we don’t seem to mind that. Maybe it is all about what we expect and don’t expect about film, that cuts across Bresson’s purpose in many of his films. For me it does in Balthazar and The Devil, though not in The Pickpocket [YouTube ].

A problem – if one can call it one – is the intellectual pre-requisites these films seen to require, particularly the theology. Not dissimilar to needing a degree in art history in order to get the full benefit from looking at renaissance paintings. Maybe that’s just called having a proper education! Or is this leading inexorably to “some films are for a narrow elite” ?

Even a poor man’s guide through the wiki links shows that Jansenists were Augustinian, and Augustine didn’t believe an individual has the ability to chose to be good, so obtaining salvation without God’s assistance. I suspect – though what do I know? – Bresson is in the territory of the City of Man and the City of God. He places a character in the City of God in a film that is clearly in the City of Man.

The heresy of Jansenism, meaning here its denial of Catholic doctrine, is that it denies the role of free will in the acceptance and use of grace—that God’s role in the infusion of grace is such that it cannot be resisted and does not require human assent. The Catholic teaching is that "God’s free initiative demands man’s free response" (CCC 2002)[3]—that is, the gift of grace can be resisted, and requires human assent.

That came from wiki:Jansenism.

Eric Mahleb’s post The Absolute Realism of Robert Bresson, is a good stopping off point here, such as:

By his own admittance, Bresson never attempted to make realistic films (‘I wish and make myself as realistic as possible, using only raw material taken from real life. But I aim at a final realism which is not realism’). His aim was to reach a certain truth, a state existing beyond the simply visible and accessible. But in the process of aiming for this truth, Bresson necessarily proclaimed an interest in the real. This desire for reality did not constitute an end in itself, only the means by which to achieve this greater goal of truth.

Mahleb goes on to discuss whether Bresson was a Jansenist: he quotes Susan Sontag: “…all of Bresson’s films have a common theme: ‘the meaning of confinement and liberty’ “.

The last part of Mahleb’s paragraph containing the Sontag quote says:

Certainly, his films are very much about seeking freedom from our bodies, bodies that constrain and restrict us in an earthly way, bodies that are subjected, poisoned and influenced by the diseases of society. Deterministic and fatalistic, Bresson’s characters have little to hope for in life except to reach Grace and the salvation it brings. Yet, it would be misleading to interpret this determinism (if one can truly talk of determinism in the context of Bresson) as necessarily pessimistic since Grace represents the ultimate, the absolute state to be reached, and thus, a positive deliverance from a society morally corrupt. Bresson does offer a way out, a dialectical escape from negativity. While the subject matters of the films may leave one with a sense of gloom upon their initial viewing, the feeling of hope and joy that underlies most of his work should more than compensate for it, as long as one is able to reach and see beyond the initial layer of ‘surface’ negativity. For instance, suicide, which occurs in several of the films, should not be looked upon as a cowardly act that ends a life but rather as an acceptable means of deliverance that enables one to reach a state of betterment. Upon watching Mouchette, we are left with no choice but to accept Mouchette’s decision to end her life as the only logical step, one that provides us with a feeling of understanding and almost complicity.

I find that very useful. Charles too in The Devil, Probably, “commits suicide”. The best touch in the film is right at the end: his friend shoots him in the back with the pistol that Charles has given him, just as Charles is about to explain exactly when he wants it to happen. He is shot in mid – sentence. We never learn what he finally wants.

Ronald Bergan, author of Sergei Eisenstein: A Life in Conflict, wrote a fascinating article in The Telegraph (13 August 1999), The filmmaker’s filmmaker, in which he quotes Bresson :

An actor, even a talented actor, gives us too simple an image of a human being, and therefore a false image.

Bresson seems to have this the wrong way round. Great actors always put something extra into film which brings it to life, even if we sometimes recognise they are too good to be true. Art needing artifice? For the ethologists among you, an actor can almost act as a supernormal stimulus.

And yet one sees what Bresson means. The robotic, two-dimensionality of the amateur acting simplifies the process, so that we watch (attend to) particular features of a story in a certain way dictated by the director. But as I watch Bresson I feel he does not really add anything by taking away as often as he thinks, as he must have felt so strongly he did.

To me Bresson is coming from an art aesthetic – as well as the ascetic – which he felt convinced would work in film. Though happy to watch his films because I accept his method, and want to understand his message, it never makes for comfortable viewing. It is possible to get the point of what he does without coming away with a sense of commitment: but that sense is what makes something a work of art. Who wants an exercise in film? And yet. Film is a broad spectrum. Indulging in an analogy: in the electromagnetic spectrum the human visual sector is very small. Bresson seems almost to be overlapping into the UV or infrared.

#

By some fluke, having two monitors and a good speaker system, there was during one viewing, a serendipitous, wildly just right juxtaposition of a FaceBookers video soundtrack running on one screen in synch with the final scene in The Devil, Probably on the other, in which Charles leads his friend to the cemetery he has chosen to die in. (In some Bresson films, there seems no point in worrying about plot spoilers, which says a lot about the style: documentary and yet not documentary; always an essay about film.) Putting a selection of popular music to the film as happened here by chance (a 5-minute short/music video by Mohamed Al Ajami accessible in FaceBook) would radically transform even what many watchers or re-watchers of Bresson are calling outdated, and without a single visual edit. Not Bresson, but interesting. It shows how the relative quiet in Bresson shows up the starkness of the amateur acting. Music, louder music, whether meant to be responded to the characters or diegetic, seems to take away some of this, and yet not detract from the story. Just make it more bearable.

Bresson can never be out of date despite this remark because he deals in universal themes.

#

Bergan begins his piece with:

Robert Bresson is among the few film directors who have an adjective named after them. Like Capraesque and Hitchcockian, a whole world is immediately conjured up by the epithet Bressonian.

which is true.

He continues:

One definition of Bressonian reads: "Derived from the films of French director Robert Bresson, to describe a pristine, formal photographic style of cinema in which expressionless, non-professional actors personify the Catholic themes of transgression, redemption and grace. "

Samuel Cooper in his blog, Boredom is Always Counter-revolutionary, writes of The Devil, Probably (8 February 2010)

Rewatching Robert Bresson’s Le Diable, Probablement (The Devil, Probably 1977) recently, it struck me that this is a film out of time; or, more precisely, a vision that is neither today’s prehistory nor a premonition of tomorrow. By which I do not mean so much that it is either ahead of its time or behind the times. Instead, having chosen to distance themselves from an immediate engagement with the corporeal present, the film’s characters are suspended between the past and the future. They reject the status quo, but also they reject any alternative or any action against the status quo, resulting in an unhappy limbo of nihilistic conservatism.

Richard Hell gave a pre-screening talk on 9 November, 2002, at the YMCA Cine-Club, NYC.

In it he says:

Speaking of God, you have to when talking about Bresson. His movies feel spiritual, in the least cornball way possible. My personal definition of God is "the way things are" and that’s what it seems to me Bresson’s movies are about, as is just about all interesting art one way or another. But once you start learning about Bresson, you discover that he’s a Catholic and much is made of his beliefs in that line. Of course most French people are Catholics and it’s said that once they get you for your first few years they have you forever. Rimbaud used to write "God is sh–" on park benches. Truffaut saw Hitchcock as a Catholic filmmaker. But apparently for at least a significant part of his life Bresson was what is called a Jansenist. I know hardly anything about Catholicism though I’ve been doing a little research. There are two things I’ve found mentioned most often about Jansenism. One is the belief that all of life is predestined, and the other is that it’s possible to achieve grace but the attainment of it, the gift of it, is gratuitous–grace doesn’t necessarily go to the so-called "good." Personally, as perverse as Catholicism has always seemed to me, at this stage of my life I don’t find those beliefs strange at all. Naturally Bresson resisted being classed as a Catholic artist in a way that pretended to explain his movies. There’s an interview with Paul Schrader where Bresson gets very impatient with Calvinist Schrader’s presumptions about him. But Bresson doesn’t make a secret of his belief that life is made of predestination and chance. At first glance to many this will seem impossibly strange, but I think it can also be seen as something simple and clear and ordinary, namely a kind of humility and mercy, a kind of forgiveness and compassion, and also as even obviously true. Look at history. Has all the talk, or rather all the doctrine, changed anything? No, people are who they are and things happen as they must. It’s nobody’s fault and it doesn’t change. It’s nobody’s fault. It’s God. Or the devil, probably. It’s just how things are.

Here is the pdf of the Interview Bresson gave to Paul Schrader in 1977:

Robert Bresson, Possibly. Schrader had written a book, Transcendental Style in Film. In 1972 Bresson wrote to Schader after reading it. The interview followed and was published in Film Comment.

* This a two-part interview with Tim Cawkwell, who wrote a book called The Filmgoer’s Guide to God. Tim Cawkwell’s Cinema is his own website for essays on a variety of films and directors. The interview is long and in two parts.

In part 2 they get on to Bresson proper. But it is worth reading the whole thing from the beginning.

One quote just to whet the appetite of those like me who ‘need to know’:

One of the most arresting things for me that Bresson said is in that famous Godard/Delahaye interview: He’s asked if he’s a Jansenist and he replies “Janséniste, alors, dans le sens de dépouillement…”, i.e. in the sense of “privation”. I think he means because he’s austere and not florid, not flamboyant. He’s a Jansenist in the sense that he has an austere, stark, subtractive style. If he wants to show someone opening a door, he shows a hand on the door handle. He doesn’t show the whole figure, or the whole door.

But immediately following that Bresson says Pascal is so "important for me". So he’s not really a Jansenist here. It’s Pascal who’s important for him. Then he adds “but he’s important for everybody” and you think, “Yes but how many people have read Pascal?”

The whole of the rest of part 2, at least a 1000 words, deals with Bresson, Jansenism, and Pascal. Which leads right back to what I said at the beginning of this post: a hunch from scant information that it was St. Augustine’s theology.

Cawkwell then goes on:

Pascal argues in favour of the theology of St Augustine. He rejects two groups, the Molinists — whom no-one’s ever heard of — who were followers of Cardinal Luis de Molina (1535-1600) and who argued that God has a conditional will to save all men generally. Pascal didn’t like this because it excludes God from free will. It makes it sound like all that humans have to do is to be good and deny evil and they’re saved, so why bother with God. And at the other extreme is Calvinism. In creating men and women, God made them by an absolute will without prediction of their merit. God sent Jesus to redeem those he wished to save and to give them his grace and salvation. And God deprives of grace all those he’s resolved to damn. Pascal calls this ’insupportable’ and he’s absolutely right. It’s dreadful. You couldn’t possibly go through the world thinking “I’m going to Hell, and there’s nothing I can do about it”.

Pascal follows the Augustinian position. Cutting a long story rather too short, he interprets this as God willing absolutely to save some people and willing conditionally to damn others; that salvation comes from the will of God and damnation from the will of man.

The rest of part 2 deals in detail both with the theology and an analysis of Bresson’s various films.

** page 45 of Husserl’s Phenomenology by Dan Zahavi

explains epoché :

FILM NON-FICTION Werner Herzog

Came across some of these Herzog documentaries before but reappeared in a surf on something not that related purely serendipitously:

Mein liebster Feind – Klaus Kinski

Notes: wiki: my best Fiend

Notes: Wiki: Dieter Dengler

notes: wiki: Little Dieter needs to Fly

Extract from Denglaers’ Escape from Laos

~

There is no doubt a personality disorder called STBOS -BWNTBSTMTACAU*: I need to say about Herzog’s non-fiction that he films it in feature film style, which is in sharp contrast to the default style coming from cinema direct/cinema verite tradition. Even his colouration and mis-en-scene is big-filmic. This has a strange but satisfying effect, a kind of equivalent visual effect to the aspects of the contrapuntal in music.

With this in mind, I am a little bit disappointed with some of the music he uses, particularly in films like Lessons in Darkness. Though music can be used to almost poke fun at the cinematic. In the oily-boy story – which is as riveting as any he has made – the music is what can only call kitsch because of its relation to the visual: that is, it is not kitsch in and of itself, but becomes so when associated with the particular visuals he uses. I would be prepared to argue this one! But it does need a sort of reply that includes the details in shot (moment-by-moment) specific film terms to explain why my opinion is wrong.

The music in Dieter does work very well unlike that in Lesson in Darkness. One is reminded of Dr.Strangelove: I can’t give chapter and verse right now, but will add to this post when I re-look at some extracts of the Kubrick.

Even if one can see where Herzog is going with all the heavy music with its deeply ironic tone, it is not as one-to-one as one might think on first seeing/hearing the film. There are many layers to the symbiosis between the music and cinematography in Lost. Repeated watching highlights subtler colours within the, at first, seemingly bleeding obvious purpose to this particular set of sound backdrops.

STBOS-BWNTBSTMTACAU* = Stating The Bleeding Obvious – But Wot needs To Be Said To Make Things Absolutely Unambiguous

FILM TRUFFAUT His Myspace page

You’d expect a man like that with the vision and energy for film to find a way to tap into the social networks beyond the grave!

Here Truffault’s Myspace page, which is full of interesting stuff produced by Carletto di San Giovanni, whose own myspace is pretty fulsome too.

PHOTOGRAPHY FILM: Between four and nine pictures

Mogan Meis’s essay in The Smart Set, Quite Ripples – Capturing the moments indifferent to being captured, plucks a chord for me: a harpsichord –and not clavichord or pianoforte — kind of moment. Meis moved from an idea from Thales to a quote from Hericlatus (‘You can’t step into the same river twice’), followed by Plato’s, ‘ if the nature of things is so unstable as that, you can’t even step in the same river fronting an explanation of a photographer’s art.

A clear litte expansion on the philosophical background from Siva Prasad might help at this point.

The photographer he looks at is Paul Graham: his exhibition, A Shimmering of Possibility, at MoMa, the perfect excuse for Meis to deliver two killer paragraphs:

..human beings have been trying to figure out what makes one thing one thing and another thing another thing. In very general terms, there have always been some people who are more comfortable with Being and some people who are more comfortable with Becoming. The Being people get excited about how identity remains stable, how a chair is always a chair, a table always a table. The Becoming people are fascinated by the gray areas, the things you can’t quite categorize, the fleeting, the indefinite.

Photography, since its invention in the 19th century, has always played the role of a double agent. On one hand, photography fixes time, a notoriously shifty and ever-changing phenomenon. But photography grabs time and sits it down. You could say that photography freezes moments of essence. This pleases the Being people. A photograph has a sliver of forever inside it.

and two killer sentences:

The old saying tells us that a picture is worth a thousand words. Graham, however, thinks you need somewhere between four and nine pictures.

Meis dissects the notions of being and becoming a bit more, but it was something else that occured to me: somehow the great filmmakers are and were quite aware of this ‘between four and nine pictures’.

Recently I saw an interview with Truffaut in which he was talking about 8 frame freezes: the maximum was 12 frames: more obtruded into the movie shots either side: the viewer was aware it was a still. Somehow at the optimal 8 frames, the stillness of a face amongst action is more a psychological stop than a physical one. Is the 8-frame an artifical construct of film with no parallel in real life? Perhaps an equivalent; is the sensation of a person talking to you suddenly having her sound off as one’s concentration goes from the words to the expression, and suddenly back again as some process in the brain decides to switch the sound back on, which hasn’t been off at all (so to speak).

In film we are being shown this 8-frame phenomenon as a stylisation. It has been used time and again by many directors. So why are cinematographers like Truffaut obsessed with it? For me, it runs right back to the simple pleaure of a flick book:; bored in a school classroom on a hot summer afternoon, teacher droning on, we idly draw a matchstick man in the top corner of the text book and make him move: the 8-frame splice is a reverse flicker book. It is a little bit ‘because it was there’, but it has a serious purpose, noneless.

No film-maker gets over the way film works: 24 fps. Even a photographer who has run off a rapid set of shots of a face, now finds it possible, with digital technology, to make the head move up and down with a loop of two photographs. There is something mesmerising about creating movement from stills.

Many filmmakers use a sequence of photographic stills or frames from a movie shot – in lieu of tight montage sequences – because they come to the conclusion that these stills — simply a short set of consecutive frames — played slower than 24 fps by digitally chosing say 1-3 seconds which is the poor man’s; still creating the necessary movement both in cinematographic and perceptio-cognitive (narrative) terms.

~

In a short documentary I am making, after much playing around with one sequence of someone arriving on a train, decamping, and walking back up the station to where I, the cameraman, am standing, I came to the slow conclusion it was more effective as film not just to show the sequence at normal speed (the edited shot with only a few seconds taken off each end), but also a repetiton of the same shot in single frames at an optimal fps to produce an inexorable slow movement forward, which at the same time was seen as a set of ever changing stills.

Such a design is always self-reflexive: that is so much what the fun of filmmaking is. In some cases, the auteur seems to be almost solely concerned with cinematographic reflexivity. No crime. The medium itself has it built into its DNA. The films such people make are as much about the pressure and satisfaction in the making as any subsequent viewing by a third party. True of all creative art.

~

In the process of running a sequence of screen grabs, one is consciously aware that this is what it must have been like for the first filmmakers – and their enchantment with the new medium – as they ran their celloid through a projector. The movie made of stills or screen grabs, though often run quite slow, is smoother than the flickering of those films at less than otpimum speed. One is fully aware, as all this happens, that one is watching how movie works, but also fully conscious immediately, or in slow stages, what it can and can’t do.

~

If I was teaching film (not likely) these are aspects of film-making I would emphasise: practical exercises with HDV cameras, each student would be told to go out and film and bring to class to work on: a few tricks to encourage the enjoyment of the filming such as how to film continuously, panning and zooming at the places where they envisioned cuts for example, to prevent them wasting too much time switching the camera on and off (and missing some of the action in the process) in the attempt to create ready made and editable shots.

~

Creating movie sequences from stills is quite a laborious process, involving grabbing maybe as many as 50 – 100 digital ‘frames’ for a 20-30 second shot. It is only when the slow motion sequence is played and replayed that it can become apparent how other elements such as music can subtly but radically alter the images.

In this specific case, I found quite quickly – almost by chance – a backing track from music site Jamendo that moved forward at the same speed as the slow movement of the stills. This sequence lasts about 30 seconds, which would be considered incredibly long by some ‘default’ filmmakers. But the slow pace of the figure moving up the station platform, facial expression slowly changing, physical actions – the posture of the body in relation to limbs – is enhanced by the perfect matching of the pace of the film with the music.

You must be logged in to post a comment.